In the 1970s, Arab royalties would often come to India for falconry, a sport that involved shooting of birds like the Great Indian Bustard, commonly found then in Western Rajasthan. It is believed that the Indian government extended this invitation to the Arabs, as a diplomatic gesture but it came to an abrupt end when in the late 70s there was a huge public outcry over the hunting of the birds. The Rajasthan Government discontinued this tradition, thus saving hundreds of Great Indian Bustards (GIBs). 40 years later, these birds are again in need of a public outcry and help, this time not just to save a few but the entire species from extinction.

From over 1200 in 1969, there are hardly 200 (or lesser) GIBs in India today. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has marked them as Critically Endangered and as one of the rarest birds in the world. Surprisingly, despite being the only nation in the world where these particular bustards are found, India has made little to no progress – even after the IUCN warning, to save them from the fast approaching dooms day.

Read More: From Dogs to Humans, Problems Galore for Great Indian Bustard

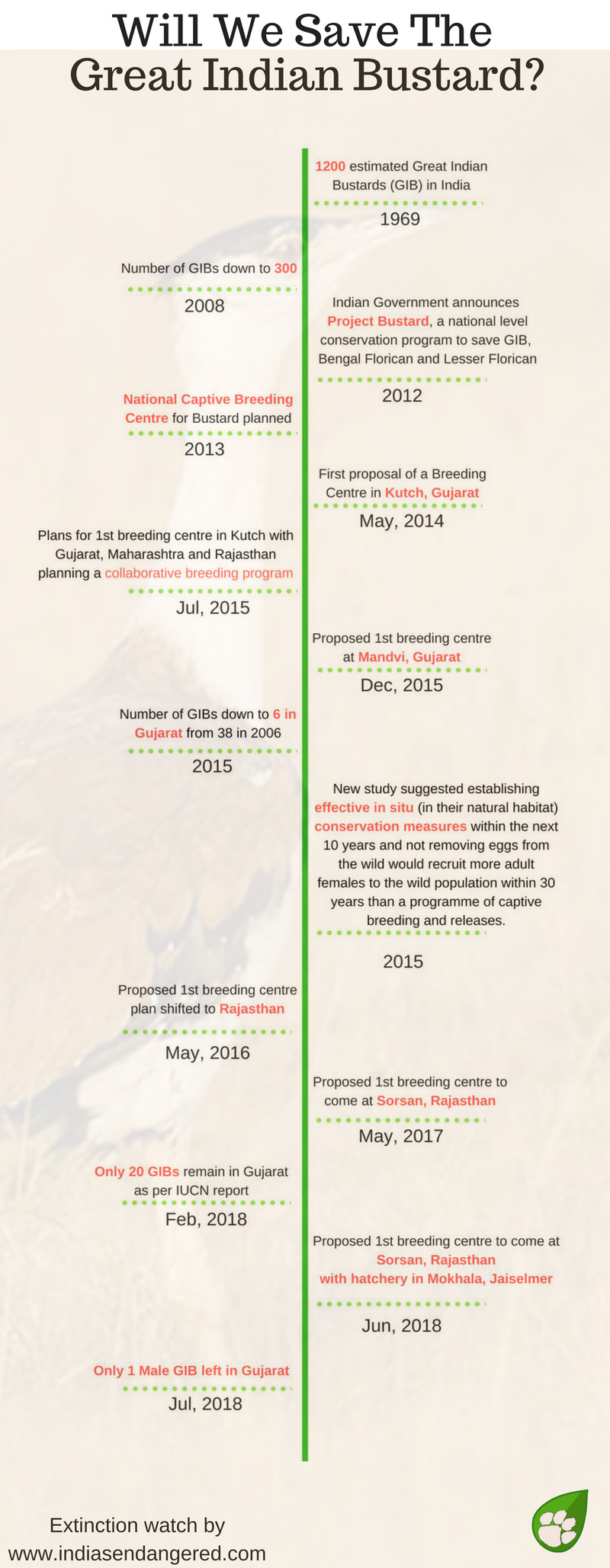

Since 2012, India launched Project Bustard in the lines of Project Tiger but 6 years and a million promises later, the bird numbers are still declining. Some experts have predicted that this giant bird could be extinct in this very century. What makes this prediction scarier is the worrisome revelation by a team of scientists who found only a single male bustard in Kutch last month.

Below is a timeline of the conservation plans India has been making for some time now that are still on papers waiting to cut through red tapism and inter-state tiffs.

Meanwhile, the problems for the Great Indian Bustard are only escalating. Without habitats, without safe place to nest, and now threatened by windmills too! Take a look,

1. Lost Habitat

According to WWF India, historically, the Great Indian bustard was distributed throughout Western India, spanning 11 states, as well as parts of Pakistan. Its stronghold was once the Thar Desert in the north-west and the Deccan plateau of the peninsula. Today, its population is confined mostly to Rajasthan and Gujarat. Small population occur in Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

Bustards generally favour flat open landscapes with minimal visual obstruction and disturbance, therefore adapt well in grasslands. However, since independence, India has lost grasslands to farmlands, urbanisation and road widening, especially so when grasslands were marked as ‘wastelands’ by policymakers. Presently, the population of the Great Indian Bustard is highest in Rajasthan’s Desert National Park, which is protected grassland area.

2. Windmills

India plans to source 40% of its energy needs through renewable energy resources by 2030 and while the move is commendable, the proliferating wind and solar farms in the western states of the country are posing a threat to the Bustard. There have been 7 bustard collisions and deaths in the last few years due to the bird flying directly towards the windmills. For a species that is critically endangered, this is nothing less than an ecological catastrophe.

Read More: Mining a Death Knell for the Great Indian Bustard

3. Agriculture

Widespread agricultural expansion and mechanization of farming have converted prime bustard habitats – the grasslands into farmlands. As per IUCN, with increased availability of water due to Government irrigation policies, agriculture has spread over vast arid–semiarid grasslands. For example, the Indira Gandhi Nahar Project has caused drastic hydraulic changes and massive agricultural conversion in and around the Desert National Park Sanctuary. Moreover, irrigation facilities and changing lifestyles have led to a shift in the crop pattern from bustard–friendly traditional monsoonal crops (sorghum, millet, etc.) to cash crops (sugarcane, grapes, cotton, horticulture, etc.) which are not suitable for the species.

4. Afforestation

Although this seems like a surprising addition to the list, the Great Indian Bustard is actually loosing not gaining habitats because of afforestation. As IUCN remarks, traditionally, grasslands and scrub have been considered as wasteland and the Forest Department policy, until recently, has been to convert them to forests with plantation of fuel/fodder shrub/tree species, even exotics like Prosopis juliflora, Acacia tortilis, Gliricidia and Eucalyptus spp., under social forestry and compensatory afforestation schemes (Forest (Conservation) Act 1988; Indian Forest Act 1927) resulting in further loss of habitat. Afforestation has been highlighted as a problem at five sites used by the species: Thar desert (Rajasthan), Naliya (Gujarat), Nannaj (Maharashtra), Ranibennur (Kamataka) and Rollapadu (Andhra Pradesh)

5. Urbanisation

Growth of industries, roadways, railways, mining, quarrying, conversion of grasslands to power projects have all had a negative impact on the bustard population. And what is left of the home is either fragmented pockets between huge industrial hubs, solar farms, wind farms and farms, or too small a land to ensure species revival.

Read More: Don’t Be Extinct Yet, The Bustard Breeding Centre is Coming Soon

6. Feral Dogs

The Great Indian Bustard breeds once in every two years an lays just one egg. Each egg is therefore of immense value but under threat of being eaten or destroyed by feral dogs present in the areas where the bustards are nesting. What makes it an even bigger challenge to avoid the dogs is the fact that the bustards make nests on the ground.

The countdown for the Great Indian Bustard extinction has already begun. If strong actions are not taken today, tomorrow could be too late.

2 thoughts on “The Perils Of Being A Great Indian Bustard”