There is a different Ganga for everyone. For the fisherman, it is his source of daily sustenance. For the septuagenarian, her gateway to Nirvana. From the washerman’s daily grime to the sins known only to the one eager to cleanse his soul, the River Ganga is at work 24×7 washing away the dirt and reviving soiled clothes, bodies, and souls.

But look beyond the surface overflowing with human activities, and you witness an aquatic diaspora living a parallel life underneath. It is the world of the turtles and the fish; the frogs and the molluscs that call the river their home. And amidst them, there is also the freshwater dolphin – the most ancient inhabitant of the revered river that has moulded itself to suit the temperament of the multi-faceted Ganges, and through generations of chiselling and shaping transformed into an animal that is truly the river’s offspring.

Declared as the National Aquatic Animal in 2009, this year, on October 5, Ganges River Dolphin Day the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) announced Dolphin Jalaj Safari, as an eco-tourism initiative to preserve the Ganga and its endangered dolphin. The safari would be conducted in six cities, namely, Bijnor, Brijghat, Prayagraj, and Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, Kahalgaon in Bihar, and Bandel in West Bengal. You can hire a boat in any of these cities and with the help of ‘Ganga Praharis’ the volunteers working towards Ganga’s cleanliness, ride the river to spot a dolphin.

But there is a difference between spotting a dolphin on the sea coast and one that lives exclusively in freshwater rivers. The most important being – its sensitivity to noises that can totally alter the way it lives, hunts, and survives.

The Freshwater Adaptations

The Ganges river dolphins have a number of features that have allowed them to live in the sometimes temulent, sometimes calm waters of the River Ganga. They have large flippers, an elongated snout, and a long neck with unfused vertebrae making it easy to bobble the head from side to side. They swim at an angle, constantly nodding their head, and sweeping the bottom of the river for food. They are also almost blind – an adaptation that seems surprising at first but immediately makes sense when you understand the habitat, they live in.

The river Ganga carries a lot of silt and sediments while flowing in the Northern plains of India. This makes visibility almost nil underwater and hence the dolphin relies more on its sense of hearing than on its sense of vision. Like bats, dolphins use echolocation to perceive objects. The click-click sounds emitted constantly is used to navigate through waters, ‘hear’ obstructions, and find prey. Naturally, they are highly susceptible to any underwater noise that may interfere with these pulses and tonal sounds.

In research published in October 2019, researchers Mayukh Dey, Jagdish Krishnaswamy, Tadamichi Morisaka & Nachiket Kelkar found out how human made noise pollution impacted the aquatic fauna. When they studied the acoustic responses of the Ganges river dolphin to the noise created by the vessels on the river, they found that the “Increase in ambient noise levels altered dolphin acoustic responses, strongly masked echolocation clicks, and more than doubled metabolic stress. Noise impacts were further aggravated during dry-season river depth reduction.”

Responding to the present initiative of the Dolphin safari, Mayukh Dey, who is currently a research affiliate with Nature Conservation Foundation says, “The Ganga, as you know, already experiences an enormous load in terms of motorised vessel traffic. The most obvious concern is that any increase in the vessel traffic may cause more harm than the intended good. Not only will the number of vessels plying in the river increase, but these will mostly be periodic travels and thus would represent a rather chronic noise environment, as opposed to a vessel that just passes by once.”

The researcher adds that their studies have shown that the most stressful time for river dolphins seem to be the drier months of the year (March onwards), as the amount of water in the river is extremely low, with a simultaneous increase in vessel traffic. Basically, there is a wall of noise during the dry season and dolphins change their behaviour completely. Since Ganges river dolphins rely almost exclusively on sound for their functioning, this can be potentially threatening for the animals. During these months, river dolphins don’t echolocate as often and therefore run the risk of entanglement in nets and collision with propellers. Therefore, any additional burden on the river during this season is best avoided.

However, given the present scenario, it is almost certain that tourists would want to take advantage of the new river safari especially during the summer months to overcome the heat and the lockdown woes. This would mean, regular and constant vessel movements and sounds right at the places where the dolphins reside.

Another worry that Dey highlights is the eagerness of the vessel operators to give in to the demands of the tourists for a sure-shot sighting of the animal.

“Multiple tourism ventures with the intent of education and awareness have not fared very well in India. The most common examples are that of the tourism industry revolving around tigers and even dolphins in Chilika lake and Goa. These ventures have led to serious stresses on resident dolphins and tigers,” warns Dey.

“Training of tourism and vessel operators is a must and it must be explicitly mentioned that the operators need to be able to say “no” to various demands and requests that don’t comply with the rules. Often, we have seen guides and operators going the ‘extra mile’ for tourists and these have really been physiologically harmful to the animals,” he adds.

A real cause for concern is also the waste that might be generated because of the frequent tourism activities. With a tumultuous history of waste management across the Ganga River System, it will only add to the problems if the rise in tourists also leads to the rise in waste that can cause long term harm to the dolphins and other aquatic inhabitants of the river.

Sustainable tourism

Dey believes, the Dolphin Jalaj Safari can be a welcome addition if it is carried out adhering to strict rules and regulations based on the lessons learned from past studies and the challenges any kind of tourism brings in a natural ecosystem.

Some mitigation ideas include,

1. Limiting the number of vessels on the river and encouraging shore watching

The type of vessels used will also be an important factor along with the speed at which they operate. River dolphins can be observed rather close to the banks and if the idea is to watch dolphins and educate people, shore watching is an excellent avenue! Perhaps watch towers and other vantage points can be utilised more than deploying motorised vessels. If boats are to be used, perhaps it would be best to measure the noise levels they produce and determine what vessels are relatively safe for dolphins.

2. Limiting boat rides during the drier months

Given that the river doesn’t carry much water in the dry season, abstaining from vessel activity during this crucial period can be incredibly beneficial for the river and its denizens. Shore or watch towers can very much compensate for removal of safaris.

3. Proper training of vessel operators and guides

Proper training of the operators and guides, not just with the ecology of the dolphins and the river, but also on managing the myriad of requests tourists often throw at them.

Unlike a protected landscape of national parks and sanctuaries where areas can remain unaltered from human presence, a river habitat does not come with exclusive human and animal borders. With increased vessel noise levels on the waterway already a deterrent to the safety of the dolphins, hopefully, the new safaris will be conducted keeping in mind the noise sensitivity of these mammals and not turn a conservation initiative into an additional nightmare for the animals.

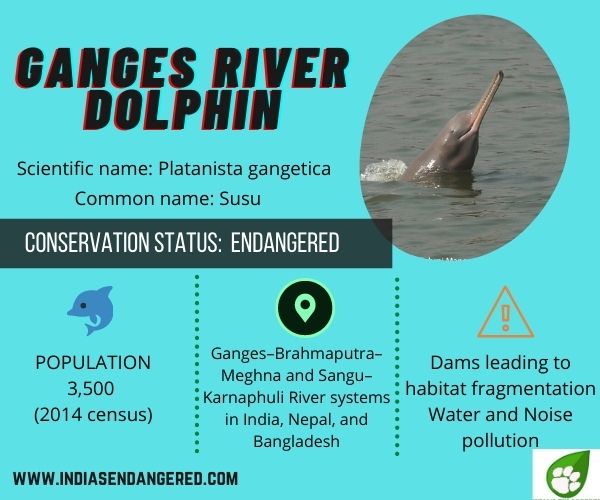

About the Ganges River Dolphin