Quick Notes

- Butterflies of peninsular India that undergo a bidirectional migration every year choose a reproductive pause to conserve energy.

- Migrating and non-migrating female butterflies have distinct morphological and physiological differences.

- A non-reproductive state helps migratory butterflies to use energy for the exhaustive 300 km migration journey from Western to Eastern Ghats.

- Post migration the butterflies breed again in large numbers and a next generation makes the return journey.

As a butterfly, there is a lot to be considered when you are only alive for 7 days. The primary concern is naturally, food, and a safe environment to live and reproduce. But what happens when you are migrating long distances as well? How do you optimise resources? This is the question scientists considered when studying the butterfly migration in peninsular India. They found that the female butterfly generation that undertake migration, have a different morphology and physiology than the regular non-migrating generations of the same species so that ultimately they can make the long distance journey safely, utilise energy optimally and be ready to breed and bring the next generation in safe conditions post migration.

The Annual Bidirectional Migration

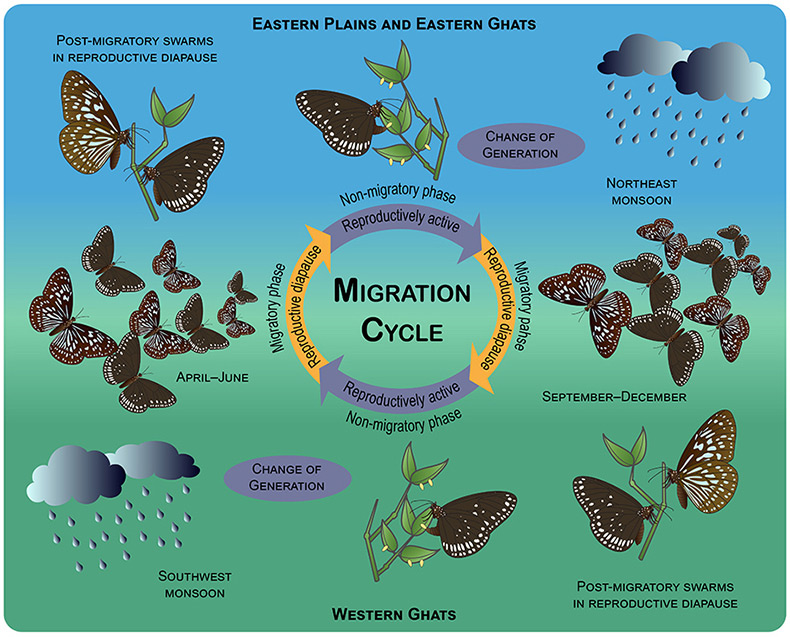

In southern India, Milkweed butterflies (so called because they feed on plants with a milky sap) are commonly found in gardens and wooded areas. Every year, four species — the Double-branded Crow (Euploea sylvester), Common Crow (Euploea core), Dark Blue Tiger (Tirumala septentrionis), and Blue Tiger (Tirumala limniace) — undertake a bidirectional migration between the Western Ghats and the southern Eastern Ghats and surrounding eastern plains. Swarms composed of millions of these butterflies can be seen in prominent cities such as Bangalore while on their way to the Eastern Ghats.

Read More: Rare Butterfly Seen After 74 Years

The first migration occurs from the Western Ghats towards the Eastern Ghats during pre-monsoon months of April to June. The return migration to the Western Ghats, undertaken by newly emerged butterflies of the next generation, takes place between October and December, after the south-west monsoons are over.

The migration of the butterflies occurs to avoid the severe south-west monsoons. They travel a distance of about 300-350 km and the journey is challenging as well as physically exhausting for the tiny insects. Still, at the end of the migration they are ready to breed and bring the next generation to the world in the suitable environs of the Eastern Ghats and hills.

How do they do this? It is through some carefully balanced investments in flight morphology and reproductive tissue that allow them to switch their physiological states and deploy fat reserves when needed.

The research was conducted by Ms. Vaishali Bhaumik, a PhD student at National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS-TIFR) and SASTRA University (Thanjavur) and her advisor Dr. Krushnamegh Kunte.

They found out typically, non-migratory butterflies start breeding within a few days after emerging from their pupae, with females growing bigger abdomens to accommodate eggs and fat tissue. Migrants, however, remain reproductively inactive during migration, i.e., in reproductive diapause. When the abdomens of the two different females were compared, the scientists found that the breeding females had a significantly bigger abdomen because of the sheer size and number of eggs they carry and the fat reserves required to sustain such an energetically costly reproductive effort.

Read More: Butterfly Park Attracts Hundreds of Colourful Winged Visitors

“Our results indicate that female butterflies may have a lot more to lose if they do not invest optimally in flight over reproduction during migration. A hiker wouldn’t carry around an unnecessarily heavy burden during her trek, and neither would a butterfly,” said Bhaumik, adding, “Migrants live longer than their resident (non-migratory) and reproductive cousins. They have distinct physiological states in their lifespans to meet the unique demands of a gruelling migratory flight, followed by reproduction.”

Another noteworthy point is that the females die soon after breeding. Therefore, in order to carry out a long distance migration, it would be wiser to pause the reproduction process, fly the long distance safely, and then breed.

The butterflies, especially the females, therefore consciously choose a non-reproductive, physiologically better shape to migrate across peninsular India with a lighter abdomen, and to produce a large number of eggs when the migration is over.

The return journey

A new generation of butterflies returns to the Western Ghats before the northeastern winter rains in November to January. However, this return migration is not frequently seen by butterfly watchers on the ground. This could be because there are fewer migrants in the returning swarms, they fly along different routes in a more loosely organized fashion, or fly at higher altitudes than those observed during the plains-ward journey in April-July.

Future work on this migration will concentrate on the climatic, behavioural, and genetic aspects, say the researchers. “We would like to find out exactly what environmental conditions drive the switch between migratory and reproductive bouts,” said Kunte. “Our ongoing investigations into any possible genetic and hormonal differences between the migratory and non-migratory populations will go a long way in explaining this phenomenon.”

Read More: Tiny National Park Showcases Huge Butterfly Diversity

This post proves that nature is full of unknown and mystery. Thanks for spreading light on such interesting facts about beautiful butterflies.

Hi I want to know about host plants for butterflies can u help me with it so I can plant them my garden to see more butterflies it might help me n them as well,

Thanks n regards