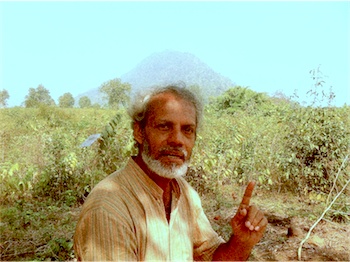

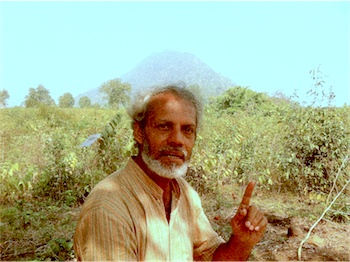

In most Indian families the daily meal seems incomplete without a bowl of rice. But while most are satisfied with their basmati and doobar, there is one man whose quest is to trace and preserve the paddy that is not commonly eaten or seen. Debal Deb has been for more than 15 years saving the most uncommon of the common rice.

In most Indian families the daily meal seems incomplete without a bowl of rice. But while most are satisfied with their basmati and doobar, there is one man whose quest is to trace and preserve the paddy that is not commonly eaten or seen. Debal Deb has been for more than 15 years saving the most uncommon of the common rice.

Back in 1995 when Debal was working at WWF he came across a study which reported that the gene pool of almost 90 per cent of local rice varieties in the country had been wiped out since the Green Revolution in 1965. Deb was aghast and found it hard to believe that while the country was concentrating on saving the tigers and the rhinos, no one seemed to notice the mass devastation of species that were no less important.

Retrieve and Preserve

Debal quit WWF and in 1996 began travelling across West Bengal in search for the rare varieties of rice that could be still saved. He shifted base to a remote town called Baliatore in Bankura district of West Bengal bordering Jharkhand.

“That was all I could afford after quitting my job. Also Baliatore was well-connected to three districts — Vardhaman, Purulia and West Medinipur — where marginalised, tribal farmers grew rare rice varieties. I decided to collect rare rice seeds from them and distribute them to other ‘modern’ farmers around West Bengal to encourage production,” he says.

Till date the lone rice savior has distributed the endemic rice varieties to over 1,200 farmers across West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Assam, Bihar, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. But the challenge was never easy.

Free Distribution

When Debal began his mission, he started contacting tribal farmers who still grew the local and wild varieties of rice because that is what they could afford. These farmers also did not have access to modern pesticides and grew what they knew would grow well in their localities. Debal took the grains from these farmers and began distributing it to other farmers without charging them any fee for the seeds.

Deb thought that the grains were not his to begin with and what he was doing was simply spreading the reach of the local seeds so that they did not die out. But soon he found that the farmers, whom he gave the seeds to, did not take much interest in sowing the seeds.

“I realised they didn’t value the seeds because they came free.”

That’s when, in 2001, he bought 1.8 acres of land in Bankura and started a seed farm called Vasudha.

“Commercially, we have no access to more than 860 rare folk rice seed varieties. I grow 600 varieties at Vasudha and, in Orissa alone, more than 200 farmers receive over 150 varieties of rice seeds,” he says.

The ecologist has an untiring devotion to his mission. That is why he keeps travelling to remote parts of the country to gain access to seeds that are not commercially available but grown by tribal farmers in some offbeat destination.

“Once, I walked 13 km in search of a farmer who had a rare folk rice seed. But when I reached his home, he had passed away. His son then destroyed his folk rice seeds and ‘modernised’ the setup,” he rues. “I am against the attitude that all things modern are good while everything that is traditional is unscientific — so let’s convert our farming regardless of the damage to productivity.”

The Hardy Survivors

Debal strongly feels that the local and wild varieities of rice might not be given huge yields but are much more resilient. He gives the example of the floods of South Bengal. He says that while the hybrid crops of rice are annually destroyed in the floods, the rare varieties survive.

“There are eight old, rare folk rice seed varieties that can be cultivated even if your farm has been washed away by a flood and the water level has reached up to 15 ft. The stem of this variety rises up to 18 ft, and no modern hybrid seed can boast of this.”

In Jharkhand, Deb distributes 15 seed varieties that can be grown in laterite soil even if the area receives 20 mm rainfall. In 2009, after the Aila storm devastated the Sunderbans, Deb distributed folk seed varieties to the farmers there, and rice grew just fine.

Presently, the ecologist works as a visiting faculty in various foreign universities, which are the only source of his income. He also regularly conducts workshops for farmers about community ethos and its role in preserving traditional methods. With his help, villagers in over 12 districts of West Bengal have formed 2,000 sacred groves (forest fragments that have a significant religious connotation for the community that vows to protect it).

“Construction of roads and power lines destroys these areas which are home to many endangered species of plants and animals,” says Deb.

But Debal does not think the urban elite will understand his mission.

“I am more comfortable working with farmers, because they can directly take this cause ahead. I am not really sure how many members of the urban elite will change their lifestyle to preserve rice seeds,” he says, with a smile.

He might be wrong in this assumption. If urban society is more open to using rice varieties that are local and not the standard commercial crops, the farmers might get the boost they need to give equal importance to these species. But while this scenario is yet to become a reality, Debal Deb continues to save the grains for the future.

More Related stories,

Maharasthra’s Biodiversity Revealed

Over harvesting Killing Life saving Plants

“With his help, villagers in over 12 districts of West Bengal have formed 2,000 sacred groves…” – Here is an error in the report: The villagers did not FORM or create any sacred groves; they PRESERVED them and PROTECTED these ancient groves from the assault of development.

Thank you sir for the correction. Your work is an inspiration to many others. Our best wishes for your mission.

Hi I as an urban Indian would like to buy Indian native varieties of rice but I am unaware of what to ask for in a market. Like if there’s a guide or a list of native varieties of rice and vegetable database we can look it up and buy it for ourselves. It would be great if we receive some help on this.

thanks

Hi Soumondeep, We suggest you contact Debal Deb or his team through their website http://www.cintdis.org/ to get more information on the native rice species that are available for commercial use and sale.

Since July 2012, Dr. Deb has made giant strides in his conservation efforts … it be best that you speak to him directly on this as some of the developments have confidentiality concerns …. but as his student and follower, I could not help sharing this with you. The seed bank for paddy has swollen to 1050 varieties … tissue culture for protection of a last-standing species of tree is on …. overall, the world seems to be swimming his way .. and yes, you are right in your article, the urban people are seeing the truth in his teachings .. like me, a 50 year old corporate lawyer, who has just begun seeing the real reality …

Thank you for your valuable information. Indeed, Dr. Deb’s contribution is immense in this field. If not for a few dedicated men like him, the world would be losing vital species without even anyone knowing about them.